The City Museum, opened on May 16, 1999, is located in the ancient Tower of St. Agnes and the adjacent small building.

The tower is one of the oldest structures in medieval Portogruaro, bought by the Municipal Administration in 1987 and carefully restored in the following years to ensure its complete usability. It is open to visitors thanks to the care and collaboration of the Pro Loco Portogruaro. The building, dating back to the 13th century, is one of the three surviving towers in Portogruaro.

In medieval times, the city was protected by a city wall, demolished definitively in 1911, characterized by five gates that allowed access to the city (Sant'Agnese, San Giovanni, San Gottardo, San Nicolò - demolished in 1886 - and a last tower was positioned on the road leading to Summaga).

The historical and artistic heritage preserved in the city museum mainly comes from the non-archaeological collections of the National Museum Concordiese of Portogruaro (Via Seminario, 26). At the entrance, visitors are greeted by representations and large-scale images of Portogruaro from the 15th and 16th centuries, the Mills, and the Municipal Palace.

Additionally, on the ground floor, a series of publications curated by various cultural associations that have reconstructed the city's history over time are collected. Inside the museum, divided into sections and chronologically homogeneous nuclei, visitors can admire stone works (patens, coats of arms, statues, inscriptions, and tombstones), metal objects (weapons, utensils, seals, and medals), and some specimens in glass and ceramics mostly dating back to the 18th century.

The noble coats of arms in stone represent one of the largest collections among the exhibited materials, totaling 15 specimens placed, for the most part, on the external walls of the Museum facing the small courtyard.

Originally, they were all surely placed on the facades of the residential buildings, or anyway owned by the families they represent; some of them still have on the back the iron ring through which they were threaded onto a support, also metallic, protruding from the wall to which they were destined. It is practically impossible to identify the buildings of origin, while it is easier to attribute them to the respective families thanks to a series of drawings, almost certainly made in the twentieth century, which reproduce the coats of arms, often completing them with the name of the family. Among all the examples, the most notable ones are highlighted. - The coat of arms attributed to the Della Gatta, in the shape of a horizontally divided shield, depicts a crouching cat with a mouse in its mouth in the center. The lower half of the shield is characterized by vertical bands, while along the outer band, there is a decoration with plant motifs.

The coat of arms of the Della Torre or Torriani family on a rectangular slab, consists of a central shield inscribed in a circle depicting a crenellated tower placed on Three Steps with two intertwined flowering branches emerging from the back.

The oval emblem depicting a small tree bent under a gust of wind from a cloud resembling a blowing cherub is evocative. The family it belongs to remains to be identified.

The coats of arms of the Venier and Corner families.

Some inscriptions carved in stone, partly visible in the courtyard of the museum, partly inside, document specific events that have affected the city of Portogruaro in different epochs.

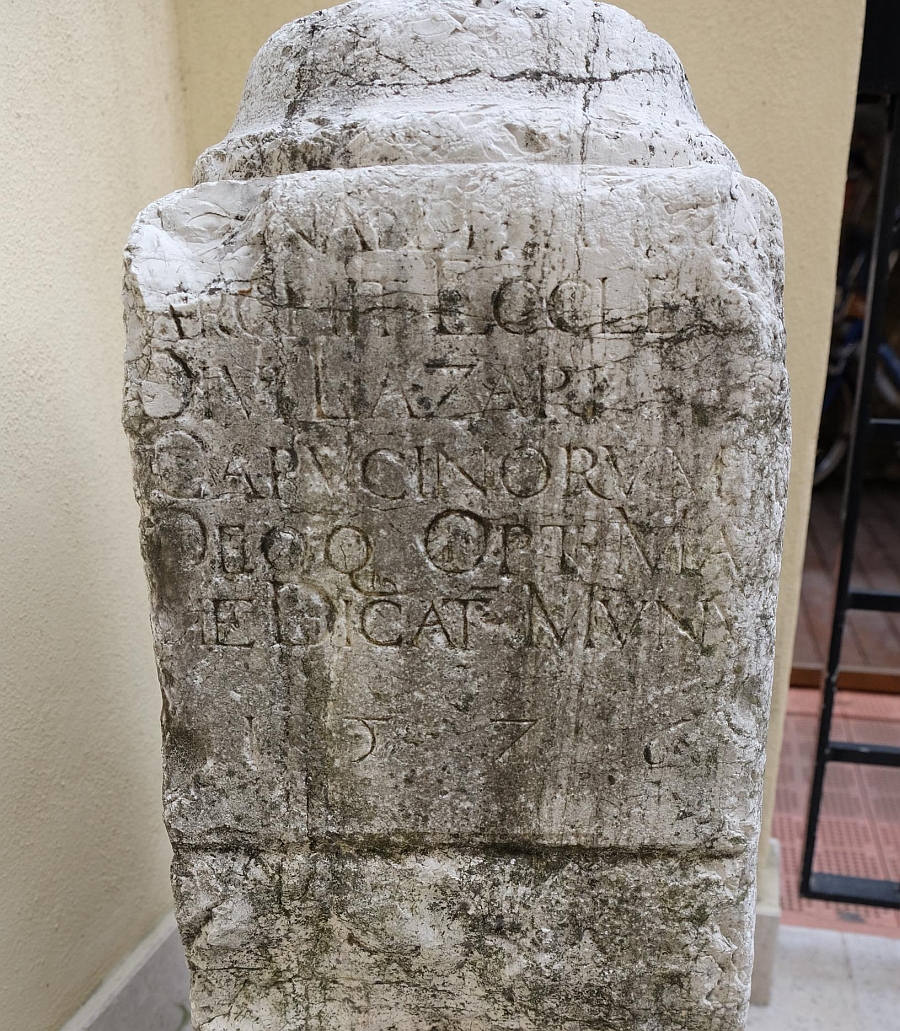

SQUARE COLUMN

A square column bears the inscription, accompanied by the date 1576, which recalls the name of Raunaldi, architect and stonemason of the Church of S. Lazzaro demolished to build the Cathedral of Portogruaro. The building, rebuilt in the 16th century by the Capuchins, was linked to the ancient hospice for lepers of S. Lazzaro, founded in the early 1200s and located outside the city walls, in the area of the current Via Zappetti, not far from the gate of S. Giovanni, already called "porta del Bando" and "porta di S. Lazzaro".

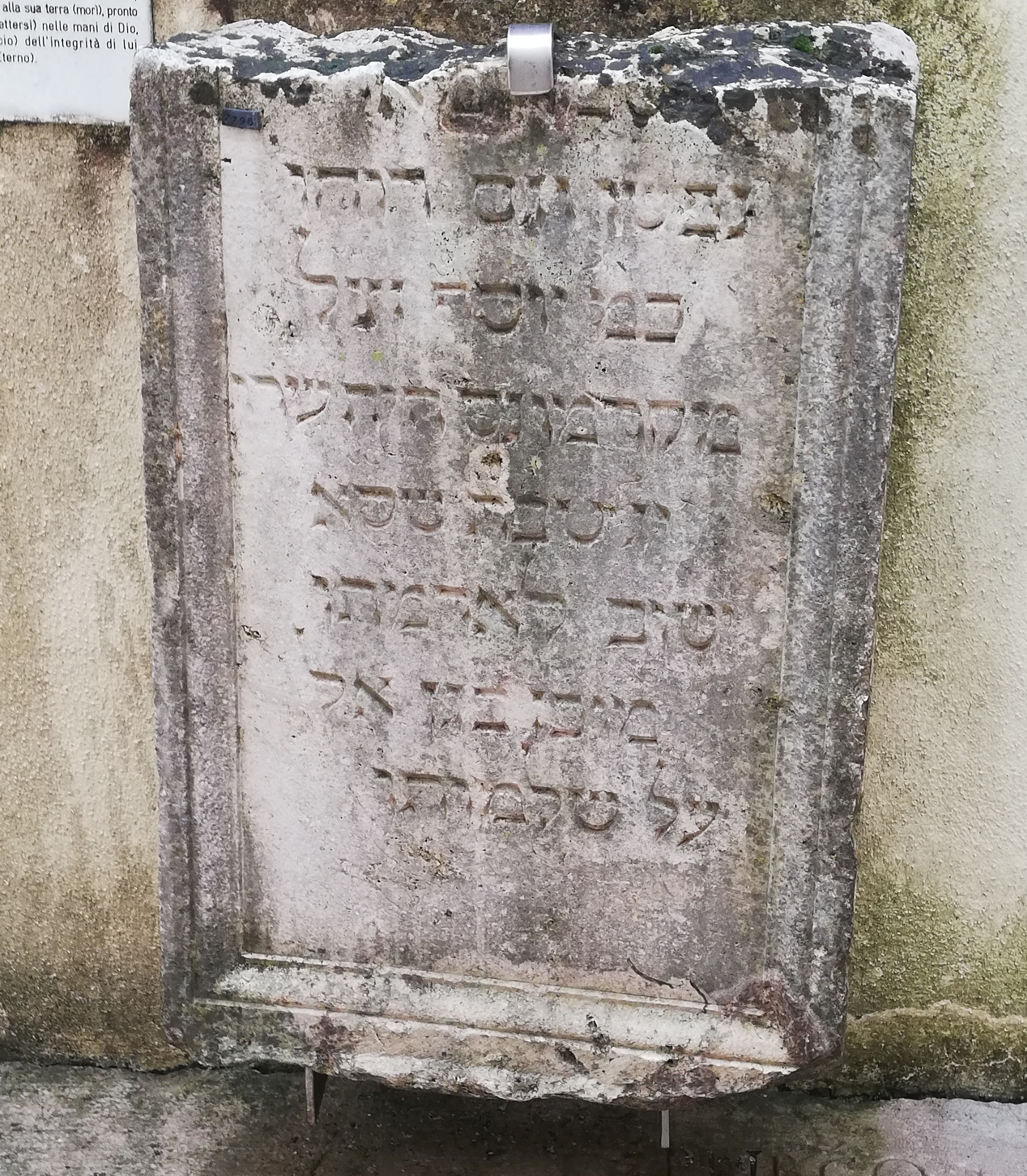

The graveston, missing some parts at the top, commemorates Zaccaria, son of Samuel Leone, who died in 1660.

Description

In the inscription, human existence is likened to a fleeting shadow pursued by death from the earliest years of life, adding that man would have nothing but tears if there were not the certainty of finding a place of relief at the moment of passing. At the top of the tombstone appears a coat of arms.

Trascription:

"Grave marking the tomb of Zaccaria,

son of Samuel Leone, (died on) 29 Tisri 5420 (1660)

Man's years are like a fleeting shadow.

Death clings to him from the moment he sees the light.

Tears (are fitting for man),

if his consolation (were not in knowing that there is) a place appointed for relief, on the day of death -

(There) the merit of my righteousness will speak in my favor;

it will be my advocate on the day of my passing,

and when I am called to judgment,

I will exclaim: 'God is with me' and I shall not fear."

- This gravestone, like the previous one at number 6, is incomplete at the top. It belongs to Giuseppe from Cormons, who died in 1601, and was possibly brought to the cemetery in Portogruaro from that area.

It is documented, indeed, in other contexts, the use of the cemetery for the burial of Jews also from other communities of Friuli, particularly from San Vito al Tagliamento. In Portogruaro, members of the Jewish community engaged in commercial activities and operated the Banco de Pegni, established by the City Council in 1575 until the establishment of the Monte di Pietà in 1666.

Trascription:

Soul and spirit did Joseph lay to rest,

(may the memory of the righteous be blessed),

He hailed from Cormons -

On the thirteenth of Tevet 5361 (1601),

he returned to his land (he died),

ready (to surrender himself) into the hands of God,

(aware) of his integrity (before the Eternal).

On the first floor, you'll find the "Pàtere" – circular stone medallions adorned with mostly zoomorphic motifs. These were originally attached to civil and religious buildings for decorative flair, defining the architectural landscape of the upper Adriatic from the 10th to the 13th centuries.

The Museum boasts ownership of 10 specimens, dating back to the 12th-13th century, predominantly crafted in marble. Their diameters span from 25 to 33 cm, with an average thickness of 8 cm. Noteworthy is the carved decoration, particularly the recurrence in three specimens, depicting the eagle triumphantly grasping either a hare or a reptile. This motif is easily interpreted as symbolizing the victory of good, embodied by the eagle, over evil, symbolized by the hare or reptile.

In the image, the Pàtera crafted from limestone portrays a snake with a scaly body, coiled upon itself. It's recognized for its unconventional subject matter, often interpreted as a symbol of malevolence and wrongdoing, yet also admired for its capacity to cleanse and rejuvenate by shedding its skin.

In the portrayal, we see the eagle, a symbol of goodness, seizing the evil embodied by the hare, depicted with remarkable expressiveness on the slightly concave-bottomed patera. Here, the meticulous attention to anatomical details of these creatures is unmistakably evident.

Furthermore, alongside the stone "patere," the museum hosts a collection of thirteen terracotta "patere" with square-shaped designs. These pieces showcase various subjects in the central panel, complemented by delicate vegetal or animal motifs adorning the outer frame.

In this 'patera', we have a depiction of a subject that repeats identically in another six specimens. It shows a mermaid seated upon the water with two tails pointing upwards, commonly interpreted as a symbol of lust."

Exposed on the first floor, this core of materials isn't very substantial and is exclusively made up of stone specimens, except for one painted wooden statue. The depicted characters are mostly saints, originally placed in city churches, but there are also examples of female figures.

The unmistakable image of Saint Peter in the statue is evident, originally bricked up and now broken in two. He is depicted with a thick wavy beard, wearing a long draped robe, holding keys in his right hand, and clutching a scroll of letters in his left.

The bust in plaster depicting a mysterious face, with a long beard and the head covered by a cloak that also envelops the shoulders, is of a profane subject.

The sandstone statue, lacking the top of the head, depicts a saint in bishop's robes, possibly St. Blaise; the gap on the head reveals a wooden pin which likely supported the mitre, a typical bishop's headgear. The saint, with a bearded face, has open and truncated arms and a slightly bent right leg; over the long robe gathered at the waist, there is a cloak fastened on the chest.

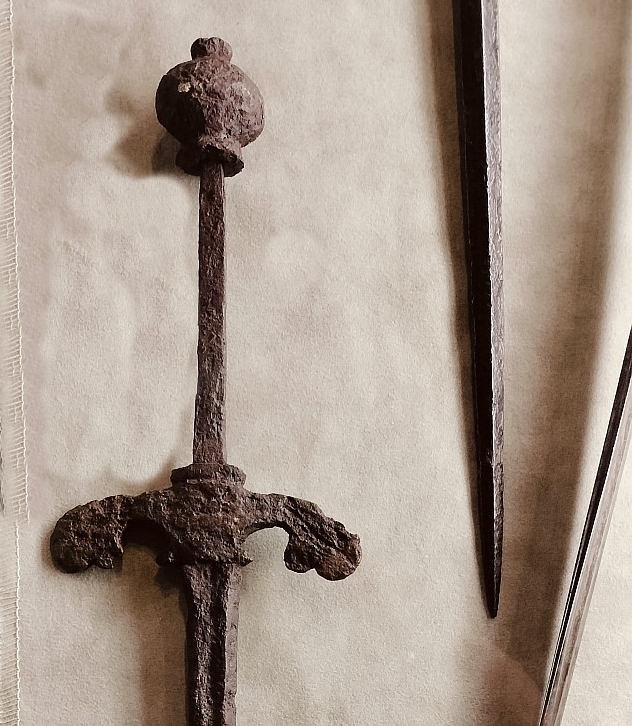

On the second floor, you can see the collection of edged weapons, mostly dating back to medieval and Renaissance periods, with some later additions.

The transition from late antiquity to the Middle Ages was marked by the introduction of swords, long spears, and polearms by so-called 'barbarian' peoples, defining the entire chronological period up to the 15th century.

In our region, similar weapons were surely employed in the defense of the many episcopal castles held by noble families from Portogruaro, Fratta, Fossalta, Gruaro, Cordovado, and so forth.

When it comes to defending rural communities, often surrounded by substantial ditches or fences, significant evidence came to light in 1989 during the excavation of the vanished parish of San Martino in the Centa di Giussago area, situated on the southern outskirts of Portogruaro. There, simple medieval iron weapons were found, such as knife blades, arrowheads, and axes, which were used as needed by the rural population along with tools like pitchforks, hoes, and scythes.

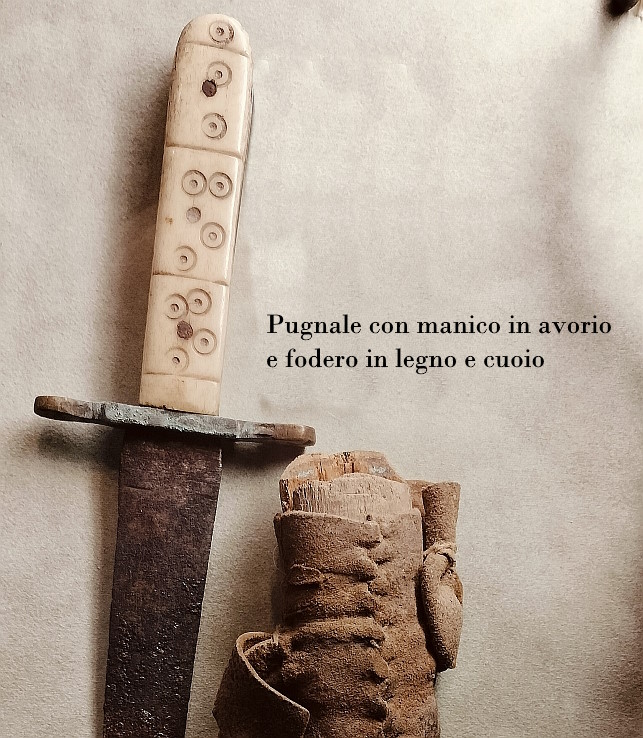

(Fig. 23) In the Renaissance era, there are two iron daggers with a triangular, sharply pointed double-edged blade, often considered as equally dangerous weapons as the stiletto and therefore prohibited. One of them has a pommel at the end of the handle and a slightly curved guard ending with a sort of vegetal motif; the other one is characterized by a lateral open ring at the handle's height.

Since the Sixteenth Century, with the spread of firearms, swords, lances, and halberds evolved into thinner swords, small swords, and hunting daggers reserved for gentlemen; whereas the common folk resorted to simpler weapons like spears, daggers, and stilettos, often finding themselves entangled in common crimes.

Complete with a sheath, two additional iron daggers (fig. 24) are presented. The initial one boasts a blade heavily oxidised, housed within a wooden sheath enveloped in leather, adorned with dual side loops. Its handle comprises twin rectangular ivory bars embellished with dice eyes. The latter showcases a conical bone handle, adorned with iron fittings at its extremity. Encased in a wooden sheath cloaked in leather, it features metallic embellishments and is equipped, at its apex, with a suspension mechanism for the weapon.

A typical example of a medieval long weapon is the double-edged sword, which lacks a handle and dates back to the 13th century. It derives from the Lombard spatha.

It was indeed bestowed upon the militias of the Bishop of Concordia, who formed a part of the army under the Patriarch of Aquileia, frequently embroiled in regional skirmishes, defending the bishoprics against the incursions of stronger and more aggressive lords. In the 18th century emerged a sword, featuring a straight and slender double-edged blade; its tip rounded, and its handle, crafted of iron mesh within, safeguarded by a curved hilt adorned with a broad connecting ring at its ends. This is a decorative and ceremonial weapon.

(fig. 25)"Very precious indeed is the saber from the 17th to 18th century, boasting a flat, slightly curved pointed blade. Its ivory handle, adorned with brass inserts, and a diminutive brass guard featuring intricately engraved floral motifs add to its allure. Moreover, atop the blade, intricate decorative engravings further enhance its mystique, proving quite challenging to decipher. In the 16th century, during the Ottoman invasions, the saber, originating from the Turkish scimitar, gained popularity in Europe. It became the primary weapon for light cavalry in the ensuing century. This particular specimen, referred to in the Venetian dialect as "paloscio," features a leather scabbard with a brass sheet covering at the tip and upper end, adorned with engraved floral motifs. Additionally, it includes a ring for attaching to the belt..

On the first floor, you'll find rather few ceramic objects adorned with geometric or figurative motifs, mostly hailing from the 18th century.

This small pedestal dish, adorned with geometric and floral motifs arranged in circular bands on the stem and base, boasts a slightly wavy molded cup. Inside, the cup is painted in blue, adorned with stylized relief yellow-painted plant elements all around, while at the bottom, a charming countryside scene with two children unfolds.

The basket, adorned with a handle, is truly a remarkable ceramic piece (fig. 30)). It boasts intricate pierced designs featuring delicate vegetal motifs and relief decorations, showcasing the skilled hands of a blacksmith crafting an arrow for the goddess Venus.

The adornments include clusters of foliage and mythical visages, though sadly some details are obscured by a sizable gap in the artifact. Its handle and interior are painted in pristine white, while the exterior showcases a striking alternation of white, blue, deep red, and green hues.

The painted glass (fig. 33) illustrates various scenes, accompanied by inscriptions, evoking the conclusion of the Republic of Venice in 1797 after the Treaty of Campoformido, the shift to Austrian governance, the brief interlude of the Kingdom of Italy during Napoleon's reign, and the restoration of Habsburg rule in 1814.

A modest assortment of items comprises predominantly handcrafted metal tools. Though pinpointing their exact age proves challenging, it is reasonably inferred that the majority harken back to the shift from the Medieval to Renaissance eras. Among these are spring-loaded toothed pliers, featuring minute teeth nestled within the jaws and a latch to fasten the arms. These spring-loaded toothed pliers (fig. 28) boast small teeth ensconced within the jaws and a latch for securing the arms.

On the second floor, there are many seals belonging to bishops, patriarchs, and doges, along with commemorative medals. These seals include those made of metal used for stamping documents, mainly belonging to the bishops of Concordia from the 18th and 19th centuries."

Additionally, there are seal marks found on wax, lead, and plaster, with the earliest ones dating back to the 14th century. Some still have the cord attached that was used to secure them to the relevant documents. Moving into the 17th century, there are a handful of lead seals that belonged to certain Venetian doges. On the obverse, they always show the same thing: the doge's picture, with 'Dux' written next to it, kneeling in front of St. Mark. The doge wears a bishop's hat and holds a flag. Sometimes, St. Mark's head is circled by a crown of stars, and his name, 'S. Marcus,' is nearby. On the reverse, the seals bear the inscription, sometimes surrounded by a simple frame, with the name of the doge followed by the expression: DEI GRATIA DUX VENETIARUM, translated: Doge of the Venetians by the grace of God; the three specimens mentioned belong to doges: Nicola Sagredo, Cristoforo Mauro, and Domenico Contarini.

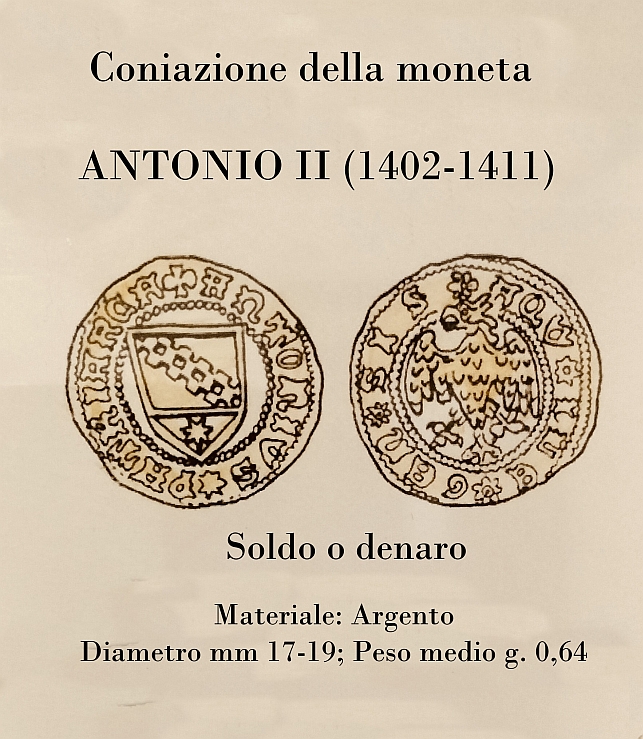

Coinage of currency ANTONIO II (1402-1411) Soldo or denaro. Material: Silver. Diameter mm. 17-19. Average weight g. 0.64

Obverse: ANTONIUS * PATRIARCA patriarch's coat of arms consists of a shield divided unevenly, with a split band of three rows in the upper part and a seven-pointed star in the lower part. Encircled by a beaded border.

Reverse:*AQV*ILE*GEN*SIS An eagle displayed with its head turned to the sinister and its tail lily-formed, interrupting with its head the beaded edge.

Until 1410, this coin had been legal tender for 12 "piccoli" and was called "soldo", circulating throughout the territory of the Serenissima and thus also in Portogruaro.

The coin was imitated by Nicholas Ujlak, King of Bosnia (1471-1477).

A bronze medal depicting St. Mark's Basilica on the occasion of its eighth centenary of construction (1894).

Some lead seals, on the other hand, belong to popes of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth centuries.

They always depict the faces of St. Peter and St. Paul on the front, placed facing each other on either side of a central cross, above which the combination of letters S P is repeated twice, clearly abbreviating the names of the two saints. On the back, sometimes enriched with a border along the edge, appears the name of the pope: in the two examples mentioned, it is Clement XIII and Leo XII.

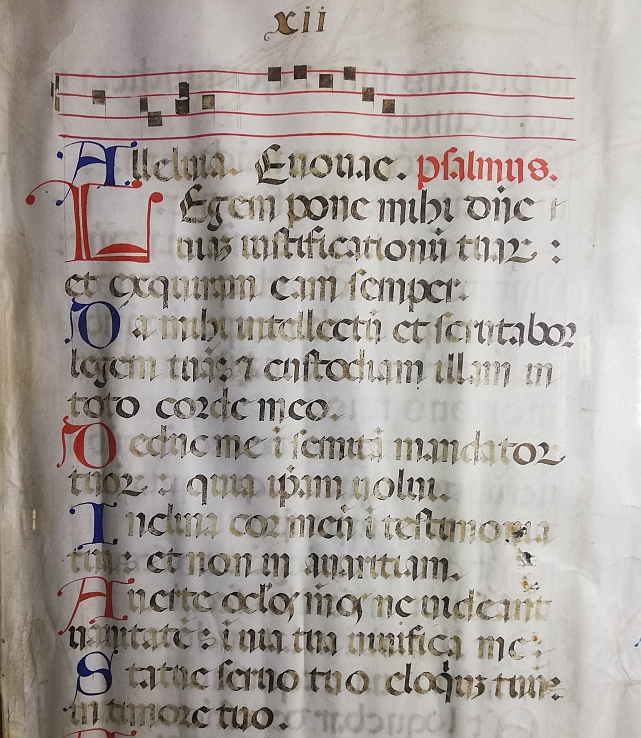

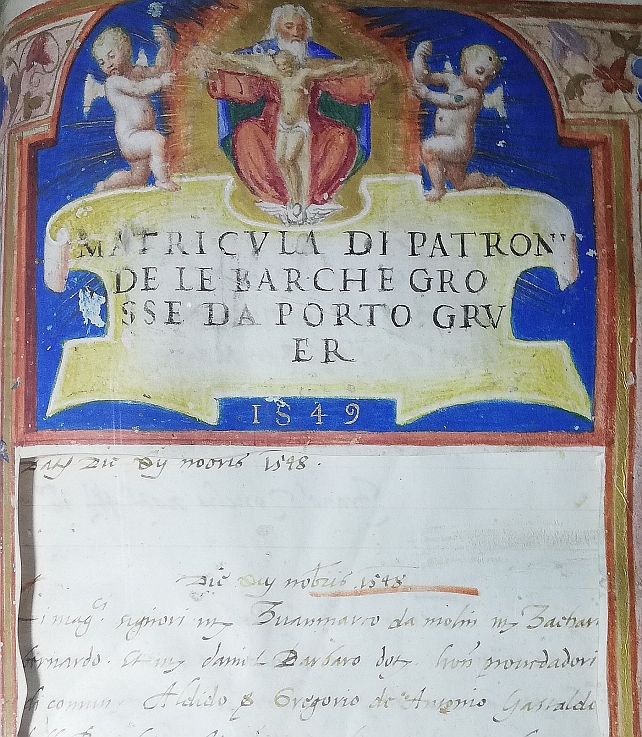

The collection of ancient manuscripts and printed publications constitutes a very rich section, arranged on the second floor.

It includes documents related to specific aspects of local history, works by local authors or about local figures, as well as more general works without direct references to the city or the area but still of great value. Some particularly notable specimens are highlighted. A portion of a manuscript on parchment (fig. 42), precisely sheets XII and XIII, of unknown origin, contains a text of the psalms and Gregorian notes on which the psalm was to be sung. All initials of the text have been made using, alternatively, red and blue ink; based on the handwriting, the manuscript can be dated to the 13th century.

The Libro dei Barcaioli (Book of Boatmen), compiled in the seventeenth century, contains an illuminated page, unfortunately cut out from its central scene. The register has a leather cover with brass applications, only half of which has survived.

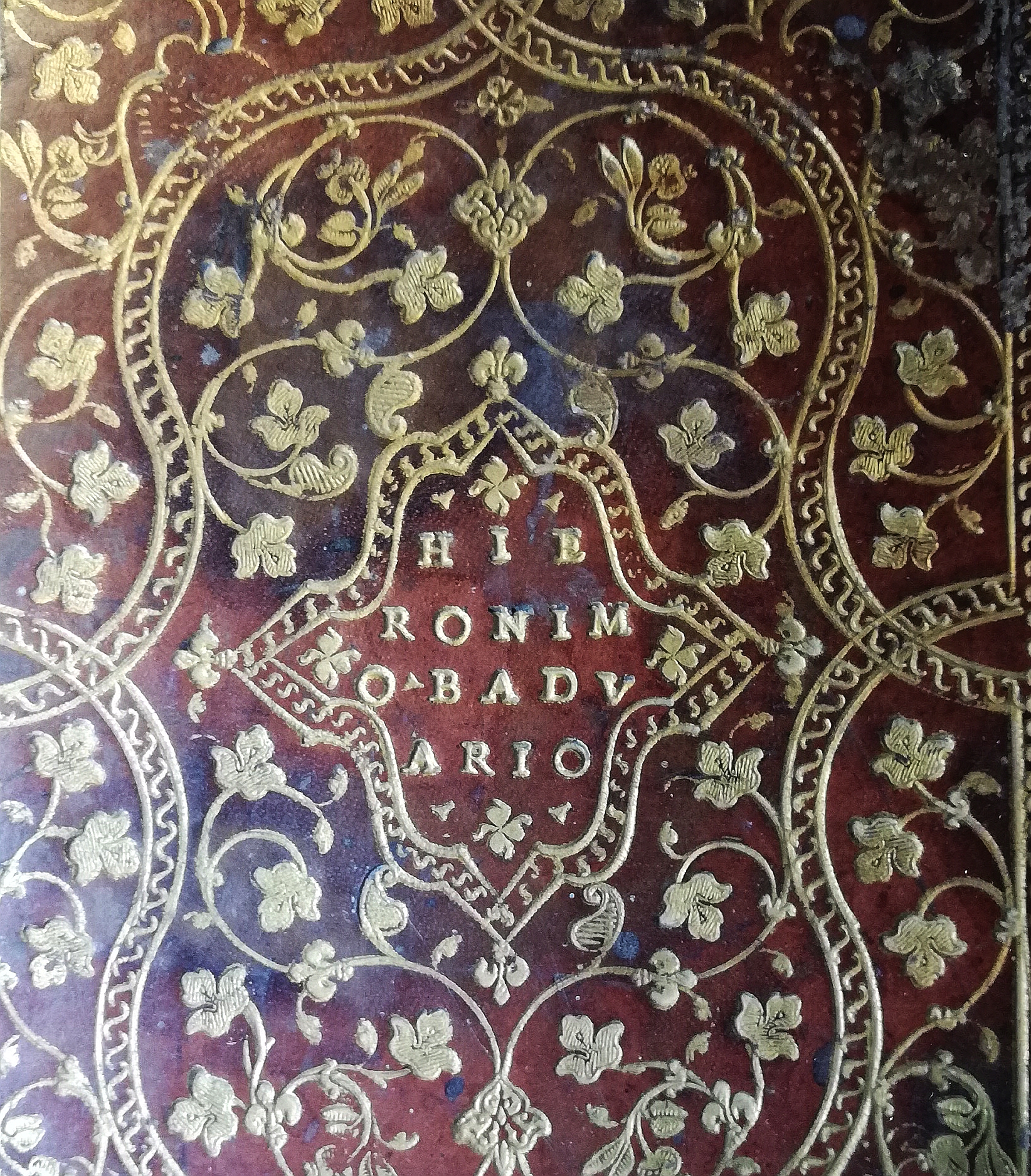

The Commission (fig. 47) of Doge Gerolamo Priuli to the Podesta of Lonigo Girolamo Badoer dates back to the second half of the sixteenth century.

The leather cover features elegant golden floral motifs and in the center the name HIERONIMO BADUARIO. The illuminated title page bears in the center the name of Doge Gerolamo Priolo, in the upper part two winged cherubs supporting the oval frame with the Venetian lion, and at the bottom, the Badoer coat of arms with the rampant lion superimposed on the transverse bands of the shield.

A momentous event was captured in the original photograph depicting the opening ceremony of the public aqueduct on 2nd February 1908 in the current Republic Square, where the monument to the Fallen had been temporarily replaced by the Pilacorte wellhead.

Count Camillo Valle, an Italian entrepreneur and politician, was born in Valdagno (Vicenza) in 1867 and died in Portogruaro in 1931. He managed the family's agricultural businesses and promoted further drainage works in the reclamation of the Venetian marshes by founding the National Federation of Reclamation, of which he was president for a long time.

For over ten years, he served as a councillor and mayor of Portogruaro, where he also held the position of podestà during the years of the regime. He was also elected to the councils of other municipalities in the province of Venice, where he served as a councillor. He participated in the First World War as a lieutenant colonel of the Alpini. He was the president of the Lugugnara Consortium, a councillor of the National Association of Reclamation and Irrigation Consortia, director of the Cooperative Agricultural Consortium of Portogruaro, a member of the Higher Council of Public Works, and president of the National Federation of Reclamation.

Valentino Turchetto was born in Portogruaro in 1906. He devoted himself to sculpture and also paid attention to the art of mosaic.

His works can be found throughout Portogruaro. Among the most well-known are: